Archive for November, 2009

Review: “Who Mourns For the Hangman?” by S. A. Bolich

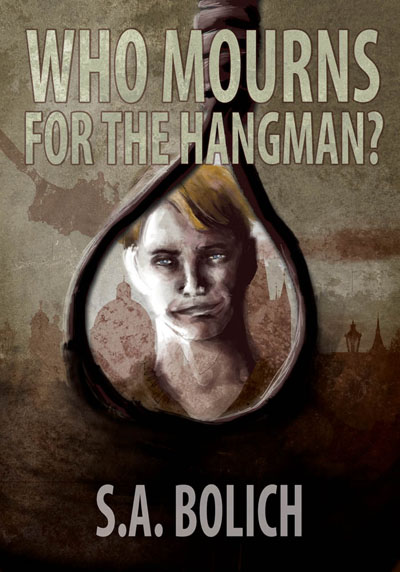

Who Mourns for the Hangman? By S. A. Bolich

"Who Mourns for the Hangman?" by S. A. Bolich

Published by Damnation Books

“Who Mourns for the Hangman?” is a novella by S. A. Bolich set in the 19th century. A hangman by the name of Scraggy Barton has been called to a town in order to hang a young man known only to him as “Young James.”

Scraggy is a hangman with a reputation. His noose glows with the power of providing justice to the people. If his noose glows, the person is a criminal, worthy of the death that he is about to receive. Having received a letter regarding this “Young James,” the noose glowed stronger than it had in the past. But will Scraggy be able to let it do its job?

This novella is extremely rich in imagery. While most writers and books on writing tell new writers to stay away from it, Ms. Bolich has masterfully used smidgens of dialect to color her story so that the readers’ suspension of disbelief even easier. The emotions of Scraggy Barton as he is faced with a situation that he never once expected are clearly described and heavily felt in the stomach of the reader.

The characters in “Who Mourns for the Hangman?” are fully fleshed out and visible in the mind’s eye as the reader ingests the words of the story. And, to answer the titular question, it is we, the readers, who mourn with the hangman as he remembers his life and choosing his work of distributing justice over that of being a father to his son, a husband to his wife.

I will be searching out more of Ms. Bolich’s work. You can find her online at her website, The official site for S.A. Bolich and follow her writing blog, Words From Thin Air.

-oo-

Kari Wolfe is a freelance author, reviewer and stay-at-home mother of the cutest little girl in the whole wide world (ok, she is a little biased). You can contact her directly at kari.j.wolfe (at) gmail.com and can find more of her work on her blog, Imperfect Clarity.

Peckinpah: An Ultraviolent Romance

Pekinpah: An Ultraviolent Romance

Book Review by Jonathan Parrish

Pigshit.

A recurring theme, hammered into your head. You wallow in it, you might say.

I couldn’t be happier. Possibly as happy as a porcine in feces. Possibly my own.

D. Harlan Wilson’s Pekinpah: An Ultraviolent Romance is not a happy read; so (to paraphrase Gary Larson) if your fridge is covered in Family Circus cartoons, you will not like it. If, on the other hand, you thought Naked Lunch was one of the best reads you’ve had, then this book has a lot of potential for you.

The book is an homage to director Sam Pekinpah, the master of slow-motion ultraviolence – a director whose imagery persists in your memory. Single scenes stake claims in parts of your mind even when the movies as a whole fade (while Convoy has not remained intact in my memory, the cafe fight scene has).

Appropriately then, Wilson weaves words into a brutal tapestry, creating a presence that will remain with you long after you stop reading. Pekinpah is confrontational and crude, with clipped sentences and stark images. The images are gritty and the progression is erratic, a series of prose paintings.

“Sky the color of uncooked fowl. Dead signage with no titles. Abandoned. Expansive gravel pit. Tread marks from pickup trucks. Tumbleweed. Skeletal trees, skeletal bushes. Telephone poles. Dead smokestacks on the outskirts. Cinderblock outhouse and concession stand in the middle of the pit, haunted by the ghosts of hotdogs, caramel corn, candy bars, Slurpees, eight lb. bowel movements… The movie screen looms over the pit. A dispossessed employee.”

The chapters describe what could be perceived as a series of scenes from a hypothetical movie. As Sam Pekinpah is no longer with us, the movie would, if it was ever made, need to be directed by David Lynch and it would be more disjointed than Eraserhead. John Woo, despite taking the mantle of slow-motion ultraviolence, would make the movie too pretty.

“Last line of the chapter—a quotation—a string of dialogue—a dark, gravely voice-over with a faint air of empathy and caring:… “We must first understand violence before we can control it.””

As disjointed as the individual pieces are, the chapters in Wilson’s book all come together into a melange, an existential love-letter to Sam Pekinpah. A more than fitting tribute. Strange. Erratic. Captivating.